THE CHANGING FACE OF OAKLAND 1945-199O

194Os: WARTIME BOOM

World War II shaped the history and growth of 20th Century Oakland as much as it came to define a chapter in American history as a whole. As for much of the United States, the economic boom brought on by the Second World War brought much-needed relief from the Great Depression of the 1930s. This boom had a huge impact on the city of Oakland in particular: Oakland’s productive port, the largest seaport in Northern California, and its strategic location at the terminus of major rail lines, made this city an important center of goods production. The wartime industries of shipbuilding and canning were producing goods at record pace during the war years, and this impressive industrial growth led to a surge in the population: there were almost 100,000 new Oakland residents between 1940-1945, and the 1945 special census revealed the population of Oakland at an all-time high of 405,301 residents[1].

Federal Housing Policies Shape Racial Geography

Wartime growth not only increased the size of the population, it increased Oakland’s diversity as well. Before the War, 3% of Oakland residents were black. But with a massive migration of both black and white shipyard workers from the Deep South, Oakland’s African-American population grew to 12% of the city’s total [3]. Bureaucratic response to this population boom would shape the the racial geography of Oakland for the years to come. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) intervened in Oakland to provide housing for the influx of migrant war-industry workers. This was no small-scale intervention: during this time the federal government created over 30,000 public housing units in the East Bay, housing 90,000 war workers and their family members [4]. Important precedents were made in housing stock patterns and in racial segregation of housing units. The FHA promoted construction of all-white suburban developments, and were not afraid to use racial covenants to carefully control the racial composition in the new developments. This left the numerous new black families of Oakland with few options. Overcrowding in West Oakland, the traditional black hub of the city, became a problem: instance of overcrowding doubled in West Oakland between 1940 and 1950 [5]. Racial homogeneity increased in West Oakland as well:

Fun Fact: Soon-to-be-famous poet Maya Angelou became one of West Oakland’s many new residents during the war years.

- In 1940, 60% of the city’s black population lived in West Oakland.

- In 1950, 80% of the black population lived in the same area (despite this population quintupling in size!)[6].

Fun Fact: Soon-to-be-famous poet Maya Angelou became one of West Oakland’s many new residents during the war years.

Death of a Key Route

Oakland’s transportation lines were subject to sinister forces during the forties. National

City Lines, a GM holding company, obtained control of 64% of the Key Route electric streetcar system in 1946, and proceeded to abolish the system through removal of street-level track, conversion of streetcar routes to diesel bus routes, and cheering the conversion of the lower deck of the Bay Bridge from public transportation to automobile use. By destroying the East Bay’s electrified public transportation system, GM removed an important barrier to the hegemony of the automobile in Oakland.

City Lines, a GM holding company, obtained control of 64% of the Key Route electric streetcar system in 1946, and proceeded to abolish the system through removal of street-level track, conversion of streetcar routes to diesel bus routes, and cheering the conversion of the lower deck of the Bay Bridge from public transportation to automobile use. By destroying the East Bay’s electrified public transportation system, GM removed an important barrier to the hegemony of the automobile in Oakland.

1950s: POSTWAR SLUMP to

1960S: STUBBORN LOCALS PREVENT REAL CHANGE

People and jobs left Oakland in the postwar years because of technological change and shifts in the housing patterns of the East Bay as a whole. Growth slowed markedly after World War II, and the 1950s brought increasing poverty and racial division in Oakland. The war’s end, as well as coming economic and technological changes, meant that industrial output slowed significantly, creating far fewer job opportunities inside the city. Postwar housing demand, along with the rise of the automobile and the implementation of the Federal highway construction program, quickened the move of Oakland residents to nearby suburbs of the East Bay whose growth had been sparked by construction of the defense worker subdivisions of WWII.

- Between 1958-66, Alameda County as a whole gained over 10,000 manufacturing jobs.

- Between 1950-70, Oakland lost nearly 10,000 jobs and 23,000 residents [8].

Race, Housing and Redevelopment

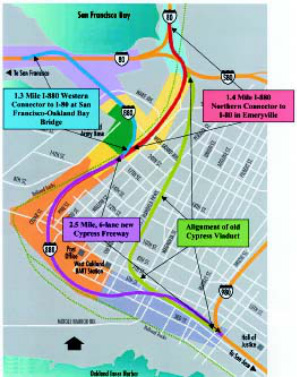

Figure 4: Aerial of demolished area to construct

Cypress Freeway[13]

With the important demographic and economic changes Oakland was undergoing in the 1950s, some saw redevelopment as the key to improving the city’s future. In 1954, executives from the industrial, banking, retail, homebuilding, and real estate sectors formed the Oakland Citizen’s Committee for Urban Renewal (OCCUR), which advocated for the creation of the Oakland Redevelopment Agency (ORA) two years later.

As with other redevelopment agencies, the ORA had the power to name which parts of the city were in need of redevelopment, claim them through the powers of eminent domain, and create plans for the new properties in the area. The ORA’s first project would be telling of its character: the Acorn Project designated about 50 blocks in West Oakland for demolition, including parts of the historic heart of black Oakland, 7th Street. On top of that, construction did not begin in Acorn until five years after demolition was completed, leaving a giant barren area in the middle of West Oakland. By the mid 60s, the demolition policies of the ORA would create deep scars in the black neighborhoods close to downtown[10].

The construction of the Cypress freeway portion of I-880 further upset West Oakland. This project, completed in 1958, demolished properties through the neighborhood in a north-south strip, pushing families out and physically segregating the westernmost section from the rest of the city. Anything but complacent, residents of West Oakland mobilized around local changes, from the way BART construction privileged suburban commuters over urban workers, to advocating for minority employment in the rapid transit system[11]. But between 1960-66, urban renewal, freeway construction, BART construction, and other government action destroyed over 7,000 housing units in Oakland, almost 5,100 of which were located in West Oakland[12].

In addition to demolition of housing stock, affordability was also an important issue in Oakland. Determining the need for public housing was not strictly a matter of crunching numbers, it was a racially charged political battle waged throughout the fifties and sixties. Redevelopers were unenthusiastic about the prospect of public housing potentially lowering property values, and it seems as though some residents and business interests were hoping that the poor would be priced out of Oakland. In 1966, though an estimated 20,000 people were eligible for public housing in the city, Oakland had just 1,422 permanent public housing units[14].

The ravaging of Oakland’s primary black neighborhood and the destruction of housing stock, along with calls to end segregation, pushed black residents out of West Oakland and raised the spectre of integration.

- Lifespan of the ORA: October 10, 1956 – February 1, 2012.

As with other redevelopment agencies, the ORA had the power to name which parts of the city were in need of redevelopment, claim them through the powers of eminent domain, and create plans for the new properties in the area. The ORA’s first project would be telling of its character: the Acorn Project designated about 50 blocks in West Oakland for demolition, including parts of the historic heart of black Oakland, 7th Street. On top of that, construction did not begin in Acorn until five years after demolition was completed, leaving a giant barren area in the middle of West Oakland. By the mid 60s, the demolition policies of the ORA would create deep scars in the black neighborhoods close to downtown[10].

The construction of the Cypress freeway portion of I-880 further upset West Oakland. This project, completed in 1958, demolished properties through the neighborhood in a north-south strip, pushing families out and physically segregating the westernmost section from the rest of the city. Anything but complacent, residents of West Oakland mobilized around local changes, from the way BART construction privileged suburban commuters over urban workers, to advocating for minority employment in the rapid transit system[11]. But between 1960-66, urban renewal, freeway construction, BART construction, and other government action destroyed over 7,000 housing units in Oakland, almost 5,100 of which were located in West Oakland[12].

In addition to demolition of housing stock, affordability was also an important issue in Oakland. Determining the need for public housing was not strictly a matter of crunching numbers, it was a racially charged political battle waged throughout the fifties and sixties. Redevelopers were unenthusiastic about the prospect of public housing potentially lowering property values, and it seems as though some residents and business interests were hoping that the poor would be priced out of Oakland. In 1966, though an estimated 20,000 people were eligible for public housing in the city, Oakland had just 1,422 permanent public housing units[14].

The ravaging of Oakland’s primary black neighborhood and the destruction of housing stock, along with calls to end segregation, pushed black residents out of West Oakland and raised the spectre of integration.

BART is Born

The state legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission in 1951, with a 26-member board with members from all nine counties that touched the bay. Six years later, the Commission advised that any plans for rapid transit in the Bay Area needed to be coordinated with a regional development plan, and the Commission created the area’s first such plan. The Commission stated that “If the Bay Area is to be preserved as a fine place to live and work, a regional rapid transit system is essential to prevent total dependence on automobiles and freeways"[15]. Construction began in 1964, after almost twenty years of discussion surrounding rapid transit in the area dating back to 1946.

Changes were also taking place in other areas of the transportation sector. Highway construction into the 1970s weakened the business districts along what had been the city’s main arteries. Additionally, the final toll for the Key Route streetcar system was heard in 1955 with the development of the AC Transit system of buses serving many of the old Key Route lines.

Three important events in Oakland planning history took place during the 1950s:

To read more about BART see: Regional Planning and Transportation.

Changes were also taking place in other areas of the transportation sector. Highway construction into the 1970s weakened the business districts along what had been the city’s main arteries. Additionally, the final toll for the Key Route streetcar system was heard in 1955 with the development of the AC Transit system of buses serving many of the old Key Route lines.

Three important events in Oakland planning history took place during the 1950s:

- The city annexed its final parcel of land in 1956.

- The Oakland Redevelopment Agency was established, also in 1956.

- The first general plan of Oakland was published in 1957, representing the city’s first master planning effort.

To read more about BART see: Regional Planning and Transportation.

The Federal Government Attempts to Create Change

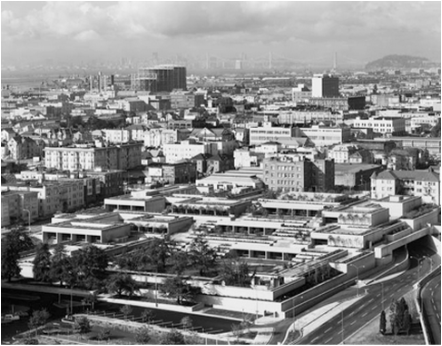

Figure 5: The modernist Oakland Museum, completed in 196917. Some projects can be successful![18]

Suburbanization represented an attempt at divestment from the urban core, and in

many ways the activism of Oakland residents marked a resistance to “urban underdevelopment” and its accompanying residential segregation, job discrimination, urban renewal, and deindustrialization[16]. Political struggles during the fifties, sixties, and seventies in Oakland reflected protracted struggles over the control of land use and economic resources by distinct communities. The city updated its general plan during 1966, potentially addressing the opportunities presented by large amounts of available federal funding (unfortunately, these plans can only be accessed at the Oakland Public Library History Room)[17] . The author of this general plan is the Oakland Planning Commission; though there is not much information on the history of the Commission, it has at least been active since the mid-1960s.

During these decades, the federal government attempted to intervene in Oakland’s lackluster and segregated job market with different programs with big budgets, sometimes up to hundreds of millions of dollars. Most notable among these projects was the Model Cities initiative, beginning 1966. Though the Model Cities’ ambitious design attempted to address a wide range of “ghetto problems,” including housing, education, and healthcare, it met the fate of most other federal programs of this time period, and was stymied by the resistance of entrenched interests. City elites privileging the downtown core were hostile to other groups gaining decision-making power, and local government repeatedly clashed with a growing number of residents and citizen’s groups.

many ways the activism of Oakland residents marked a resistance to “urban underdevelopment” and its accompanying residential segregation, job discrimination, urban renewal, and deindustrialization[16]. Political struggles during the fifties, sixties, and seventies in Oakland reflected protracted struggles over the control of land use and economic resources by distinct communities. The city updated its general plan during 1966, potentially addressing the opportunities presented by large amounts of available federal funding (unfortunately, these plans can only be accessed at the Oakland Public Library History Room)[17] . The author of this general plan is the Oakland Planning Commission; though there is not much information on the history of the Commission, it has at least been active since the mid-1960s.

During these decades, the federal government attempted to intervene in Oakland’s lackluster and segregated job market with different programs with big budgets, sometimes up to hundreds of millions of dollars. Most notable among these projects was the Model Cities initiative, beginning 1966. Though the Model Cities’ ambitious design attempted to address a wide range of “ghetto problems,” including housing, education, and healthcare, it met the fate of most other federal programs of this time period, and was stymied by the resistance of entrenched interests. City elites privileging the downtown core were hostile to other groups gaining decision-making power, and local government repeatedly clashed with a growing number of residents and citizen’s groups.

The Black Power Movement

not lead to fundamental change in segregated housing and labor markets, or challenge the discrimination of white civil society[19]. Frustrations such as this provided some of the fuel for the Black Power movement. Oakland was at the vanguard of this trend: The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, both students at Oakland City College, and the first BPP office was opened January 1st of the next year. The Panthers quickly gained thousands of party members nationwide with their forceful rejection of segregated civil society. The Panthers were also heavily invested in combating police brutality, of which there was no shortage in Oakland. Of 661 Oakland police officers in 1966, only 16 were black.

1970S AND 1980S: CHANGES DOWNTOWN

The 1970s and 1980s saw a deepening of the patterns of the fifties and sixties: large-scale demographic change remained a constant, as did continued economic divestment from the urban core and the declining number of available urban jobs.

Detrimental to the communities of Oakland was the emergence of large-scale

gang-controlled drug operations in the 1970s. Rates of violent crime skyrocketed during this decade; Oakland’s murder rate rose two times that of San Francisco or New York City during the same time period[21]. Oakland was plagued in the eighties by a continuation of the rising crime rate and drug issues of the previous decade. Crack cocaine exploded as a big problem for the city during this period, and Oakland was regularly listed as one of the U.S. cities most plagued by crime.

As mentioned above, demographic and economic changes continued to drive Oakland’s development in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Economic trends proved to be especially painful. Between 1981-88, Oakland lost 12,000 jobs in the traditional industries of utilities, transportation, manufacturing, and communications. And by the eighties, major retailers were abandoning the city:

Pronounced demographic trends also shaped the fabric of Oakland. Oakland lost 90,000 white residents between 1970 and 1990. Black population growth slowed as well as many black families moved to the suburbs, even as Oakland elected its first black mayor, Lionel Wilson, in 1977. In place of these two groups came new immigrants from Asia and Latin America. Between 1980-2000, these two groups grew from 8% and 9% of the population to 16% and 22%, respectively, producing growth in certain neighborhoods such as the heavily Latino Fruitvale district and Oakland’s Chinatown.

Detrimental to the communities of Oakland was the emergence of large-scale

gang-controlled drug operations in the 1970s. Rates of violent crime skyrocketed during this decade; Oakland’s murder rate rose two times that of San Francisco or New York City during the same time period[21]. Oakland was plagued in the eighties by a continuation of the rising crime rate and drug issues of the previous decade. Crack cocaine exploded as a big problem for the city during this period, and Oakland was regularly listed as one of the U.S. cities most plagued by crime.

As mentioned above, demographic and economic changes continued to drive Oakland’s development in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Economic trends proved to be especially painful. Between 1981-88, Oakland lost 12,000 jobs in the traditional industries of utilities, transportation, manufacturing, and communications. And by the eighties, major retailers were abandoning the city:

- In 1977, Oakland’s central business district had seven department stores.

- In 1987, only four department stores were left in the entire city[22].

Pronounced demographic trends also shaped the fabric of Oakland. Oakland lost 90,000 white residents between 1970 and 1990. Black population growth slowed as well as many black families moved to the suburbs, even as Oakland elected its first black mayor, Lionel Wilson, in 1977. In place of these two groups came new immigrants from Asia and Latin America. Between 1980-2000, these two groups grew from 8% and 9% of the population to 16% and 22%, respectively, producing growth in certain neighborhoods such as the heavily Latino Fruitvale district and Oakland’s Chinatown.

Downtown Struggles

Downtown could not keep pace with the changing city, and settled into deep decline in the 80s. Project after project failed throughout the decade, as developers failed to find tenants or encountered other planning problems:

Additionally, downtown retail vacancy rates stayed around 15% throughout the decade. City officials attempted to counteract downtown’s downward spiral: while there does not seem to have been any general plan updates during the ‘80s, both downtown and North Oakland were the subjects of neighborhood development plans, seemingly Oakland’s first such proposals. These plans can be found at the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley.

- Plans for a mall next to the City Center were abandoned in the early ‘80s when Macy’s left the project.

- Kahn’s department store, long a symbol of downtown vitality, closed in 1984, and remained boarded up for years after.

- Plans for a $350 million regional retail center were thrown out in 1985 when no retail partners could be found[23].

Additionally, downtown retail vacancy rates stayed around 15% throughout the decade. City officials attempted to counteract downtown’s downward spiral: while there does not seem to have been any general plan updates during the ‘80s, both downtown and North Oakland were the subjects of neighborhood development plans, seemingly Oakland’s first such proposals. These plans can be found at the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley.

Loma Prieta Earthquake

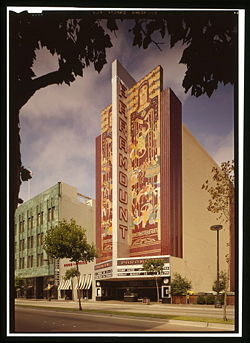

Figure 8: The Paramount Theater, post-restoration[25].

Oakland’s redevelopment efforts were foiled at every turn, even by Mother Nature. The city’s planning faced an important challenge after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, when infrastructure and a number of buildings were damaged. The city faced the task of deciding whether to conduct expensive renovations and retrofits of existing, but damaged buildings, or to demolish them. Decisions were made on a case-by-case basis, and some expensive upgrades of early twentieth century buildings were undertaken, such as to City Hall, the Tribune Tower, and the Kahn’s department store building. A large segment of the Bay Bridge was destroyed in the quake, and both the western and eastern spans of the bridge have been or currently are subject to retrofitting.

More positive developments in the 1980s include the restoration of the beautiful art deco Paramount Theater, the opening of the Transbay tube, and the designation of the first city landmark, demonstrating that some projects can still be successful even in a climate that thwarted large-scale city redevelopment and reinvention.

More positive developments in the 1980s include the restoration of the beautiful art deco Paramount Theater, the opening of the Transbay tube, and the designation of the first city landmark, demonstrating that some projects can still be successful even in a climate that thwarted large-scale city redevelopment and reinvention.

WORKS CITED_____________________________________________________

- Land Use and Transportation Element. (n.d.). City of Oakland General Plan. Retrieved February 22, 2013, from http://cdm16255.contentdm.oclc.org/utils/getfile/collection/p266301ccp2/id/688/filename/689.pdf. p. 18.

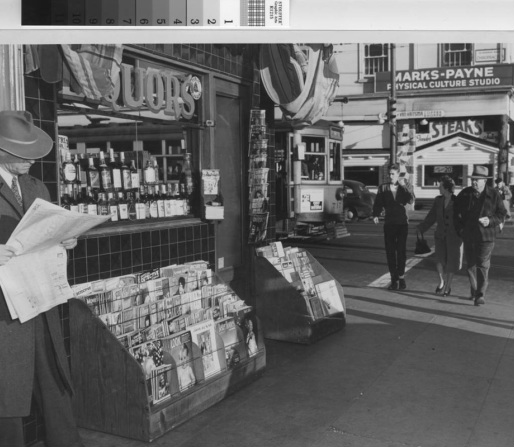

- Cohen, Moses L.. Downtown Oakland, c.1945, on the corner of 14th and Webster Streets . 1945. Oakland Public Library, Oakland History Room and Maps Division, Oakland, CA. Online Archive of California. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

- Zinko, C. (2007, September 25). WWII meant opportunity for many women, oppression for others . San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 23, 2013, from http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/WWII-meant-opportunity-for-many-women-oppression-2501118.php

- Johnson, M. S. (1993). The second gold rush Oakland and the East Bay in World War II. Berkeley: University of California Press. P. 99.

- Johnson p. 93.

- Rhomberg, C. (2004). No there there race, class, and political community in Oakland. Berkeley: University of California Press. P. 121.

- Cohen, Moses L.. Downtown Oakland, c.1945, on the corner of 14th and Webster Streets . 1945. Oakland Public Library, Oakland History Room and Maps Division, Oakland, CA. Online Archive of California. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

- Donald, H. M. Jerry Brown’s No-Nonsense New Age for Oakland, City Journal Autumn 1999. City Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2013, from http://www.city-journal.org/html/9_4_a2.html

- Department of Transportation. (n.d.). Cypress Freeway Replacement Project - Case Studies - Environmental Justice - Environment - FHWA. Home | Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2013, from http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/environmental_justice/case_studies/case5.cfm

- Rhomberg p. 125.

- Rodriguez, J. A. (1999). Rapid Transit and Community Power: West Oakland Residents Confront BART. Antipode, 31(2), 214.

- Rhomberg p. 125.

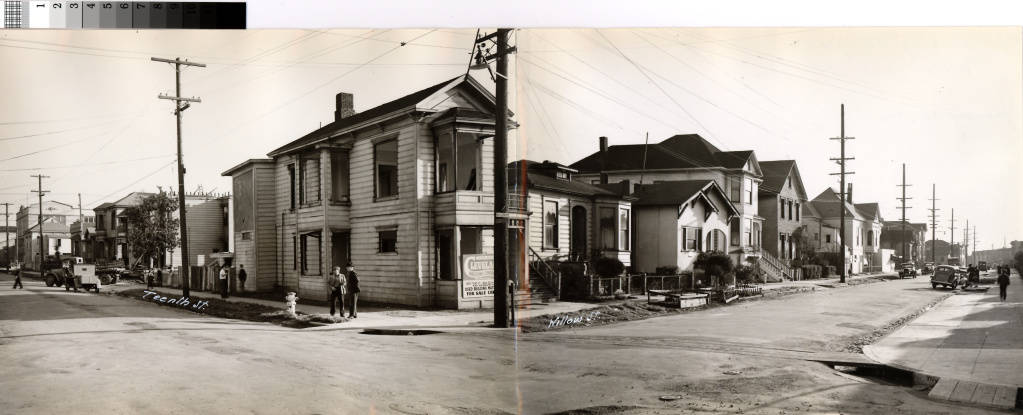

- Cypress Freeway. 1950. Oakland Tribune Collection, Oakland, CA.EcoJustice. Web. 4 Mar. 2103.

- Rhomberg p. 130.

- BART - A History of BART: The Concept is Born. BART - Bay Area Rapid Transit. Retrieved February 23, 2013, from http://www.bart.gov/about/history/index.aspx

- Self, R. O. (2003). American Babylon: race and the struggle for postwar Oakland. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- See the History Room website at http://www.oaklandlibrary.org/locations/oakland-history-room for more information

- Stoller, Ezra . Oakland Museum of California. 1968. ARTstor, Oakland, CA. ARTstor. Web. 2 Mar. 2013.

- Rhomberg p. 144.

- Jones, Pirkle. A Black Panther demonstration on July 30, 1968, at the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland during Huey P. Newton’s trial.. 1968. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Oakland, CA. The New York Times. Web. 4 Mar. 2013.

- Mac Donald

- Rhomberg p. 184.

- Rhomberg p. 184.

- Ramirez, Daniel. Oakland City Hall. 2008. Wikipedia Commons, Oakland, CA.Wikipedia. Web. 2 Mar. 2013.

- Paramount Theatre. Art Deco Society of California, Oakland, CA. Royal Society Jazz Orchestra. Web. 2 Mar. 2013.